|

Chasing pigeons in the square....> |

|

|---|---|

|

|

Heading to the Interior

Mexico is a huge country. We don't think we quite realized how big when we started this trip, or how beautiful and captivating it would be, how generous and friendly the people are, or how good the food is, etc. And it feels great to settle a bit in one place and get to know it, (we stayed 6 days in Mazatlan) but soon the open road and future adventures begin to call us and we pack up and head out again. From Mazatlan we took the steep and curvy Highway 40 east across the notorious Devil's Backbone (Espina del Diablo) through the Sierra Madre Occidental to Durango, a climb of over 7,000 feet. As the driver, Rus didn't see anything but the hairpin curves in front of him, but Kathleen tells him the views were magnificent and precipitous, deep gorges to rival the Grand Canyon, and the first pine forests we've seen in Mexico so far. On the way we remembered that our son Josef was flying to the Philippines within the hour, so we stopped at every roadside cafe (cliffside is more accurate) until we found a phone to call and wish him well. Despite all our efforts, and the help of the Senora there, we weren't able to make a connection, but we did attract the

Mexico is a huge country. We don't think we quite realized how big when we started this trip, or how beautiful and captivating it would be, how generous and friendly the people are, or how good the food is, etc. And it feels great to settle a bit in one place and get to know it, (we stayed 6 days in Mazatlan) but soon the open road and future adventures begin to call us and we pack up and head out again. From Mazatlan we took the steep and curvy Highway 40 east across the notorious Devil's Backbone (Espina del Diablo) through the Sierra Madre Occidental to Durango, a climb of over 7,000 feet. As the driver, Rus didn't see anything but the hairpin curves in front of him, but Kathleen tells him the views were magnificent and precipitous, deep gorges to rival the Grand Canyon, and the first pine forests we've seen in Mexico so far. On the way we remembered that our son Josef was flying to the Philippines within the hour, so we stopped at every roadside cafe (cliffside is more accurate) until we found a phone to call and wish him well. Despite all our efforts, and the help of the Senora there, we weren't able to make a connection, but we did attract the  interest of everyone in the village, and soon had a crowd of about 10 people gathered around the phone to watch the "drama" unfold. You can't be shy in Mexico. Situations force you to act outrageous sometimes, for example, Kathleen standing in the middle of the road, stopping traffic while she helps Rus back up for several blocks because the street suddenly became too small, or worse yet, one way! And even when you feel foolish about not knowing how simple things work, like calling a cell phone in the USA using a phone card from a pay phone, first by following explicit directions given in a Mazatlan newspaper for tourists, and then, when that didn't work, trying the advice, offered in Spanish, of a woman who really seemed to care, the foolishness melts away and is replaced by warmth or a sense of freedom. The lovely senora who helped Kathleen place the call had a 20 year old herself and when we weren't able to get through on the pay phone she brought us inside to use her private line. We never got to say goodbye to Joe but we made a new friend, got to hear her story and had a tasty homemade lunch before moving on.

interest of everyone in the village, and soon had a crowd of about 10 people gathered around the phone to watch the "drama" unfold. You can't be shy in Mexico. Situations force you to act outrageous sometimes, for example, Kathleen standing in the middle of the road, stopping traffic while she helps Rus back up for several blocks because the street suddenly became too small, or worse yet, one way! And even when you feel foolish about not knowing how simple things work, like calling a cell phone in the USA using a phone card from a pay phone, first by following explicit directions given in a Mazatlan newspaper for tourists, and then, when that didn't work, trying the advice, offered in Spanish, of a woman who really seemed to care, the foolishness melts away and is replaced by warmth or a sense of freedom. The lovely senora who helped Kathleen place the call had a 20 year old herself and when we weren't able to get through on the pay phone she brought us inside to use her private line. We never got to say goodbye to Joe but we made a new friend, got to hear her story and had a tasty homemade lunch before moving on.

Huichol Bead Painting in the Museo Zacatecano

which also features a large selection of hand-painted religious retablos

< View of Zacatecas from our hill

Arriving very relieved at the town of Durango, (pop 450,000, elevation 6,200 feet) we parked at a hotel that used to house the film crews that made many western movies around Durango in the '60's, but had since fallen on hard times. They offered a parking space for our rig, and for facilities gave us a key to one of their rooms with admonishments not to use the bed, only the bathroom. The room was large, worn but clean, and most the bathroom was marble. We feel pretty certain that John Wayne probably used the same room we did. Almost positive, but we can't say for sure. Anyway his boot and hand prints were on a concrete slab nearby, so at least maybe he saw our room!

Next day we lit out for Zacatecas, (Population 150,000, elevation 8,200 ft) the capitol of Mexico's state by the same name, a beautiful hillside colonial city built over miles of silver mine tunnels, at one time the source of 20% of Spain's silver from the New World, and still a mining center today. We were about the only gringos in town, but we saw Mexican tourists aplenty. Zacatecas unknowingly gave us the red carpet treatment. We happened upon a State competition of traditional dancing in the cathedral square that awed us with its vibrancy and the passion of the young dancers, and the next day stumbled upon an outdoor free concert by the Zacateca State Orchestra, an excellent 75 piece ensemble . Plus a lively parade of young beauties and their cheering fans drove past us, smiling for our camera and waving at us as if we were celebrities. Later a group of 6 or 7 teenagers chased us for several blocks begging to have their picture taken with us and especially Ziggy, though one girl was so afraid of her she wouldn't stand close enough to be in it.

Next day we lit out for Zacatecas, (Population 150,000, elevation 8,200 ft) the capitol of Mexico's state by the same name, a beautiful hillside colonial city built over miles of silver mine tunnels, at one time the source of 20% of Spain's silver from the New World, and still a mining center today. We were about the only gringos in town, but we saw Mexican tourists aplenty. Zacatecas unknowingly gave us the red carpet treatment. We happened upon a State competition of traditional dancing in the cathedral square that awed us with its vibrancy and the passion of the young dancers, and the next day stumbled upon an outdoor free concert by the Zacateca State Orchestra, an excellent 75 piece ensemble . Plus a lively parade of young beauties and their cheering fans drove past us, smiling for our camera and waving at us as if we were celebrities. Later a group of 6 or 7 teenagers chased us for several blocks begging to have their picture taken with us and especially Ziggy, though one girl was so afraid of her she wouldn't stand close enough to be in it.

We had a wonderful walk each day down a series of steep staircases that led to town from our hilltop hotel, which offered a few parking spaces with hookups for campers. This beautiful city is cradled by mountains, it has narrow cobbled streets that twist around the slopes or abruptly turn to steps of stone. It has lovely parks with (flowering) shade trees, fountains, benches that are almost always taken, and an abundance of flaming bougainvilleas in magenta, orange and purple. It has beautiful old pink sandstone cathedrals and an ancient aqueduct. We toured the Mina Eden where silver, copper, zinc and other minerals were mined until recently. We looked at a rather funky apartment with a panoramic view of the city for $180/mo, and toyed with the idea of staying there to study Spanish. In the end, we opted to go to San Miguel de Allende instead, where there were higher concentrations of gringos and therefore a better selection of language schools. In Zacatecas our language instructor would have been Rodrigo, the manager of these rooftop apartments, who had been our waiter in the restaurant below, a very interesting and friendly man who said he was a maestro (teacher) but who spoke with a slight slur which made him difficult to understand. Tempting, but no.

We had a wonderful walk each day down a series of steep staircases that led to town from our hilltop hotel, which offered a few parking spaces with hookups for campers. This beautiful city is cradled by mountains, it has narrow cobbled streets that twist around the slopes or abruptly turn to steps of stone. It has lovely parks with (flowering) shade trees, fountains, benches that are almost always taken, and an abundance of flaming bougainvilleas in magenta, orange and purple. It has beautiful old pink sandstone cathedrals and an ancient aqueduct. We toured the Mina Eden where silver, copper, zinc and other minerals were mined until recently. We looked at a rather funky apartment with a panoramic view of the city for $180/mo, and toyed with the idea of staying there to study Spanish. In the end, we opted to go to San Miguel de Allende instead, where there were higher concentrations of gringos and therefore a better selection of language schools. In Zacatecas our language instructor would have been Rodrigo, the manager of these rooftop apartments, who had been our waiter in the restaurant below, a very interesting and friendly man who said he was a maestro (teacher) but who spoke with a slight slur which made him difficult to understand. Tempting, but no.

Photo above:

The cathedral in Zacatecas is considered the best example of a churringueresque church in Mexico. We don't actually know what that means but we thought it quite impressive without knowing.

|

|

|---|

San Miguel de Allende

So to San Miguel de Allende (Population 65,000, Elevation 6,100 ft) we went, another lovely hillside colonial town, but with the difference of also being home to some 7,000 at least part-time expatriated gringos, or about 10% of the population, mostly seniors, not counting the additional tourists like us. A very few are assimilated into the Mexican culture, but most are isolated in luxury houses and many speak very little Spanish beyond what's required to do their shopping and give directions to gardeners, maids and other workers. On our visit to the cemetery (we often visit Mexican cemeteries), we even discovered a separate section reserved for Americans, gated off from the main area. For the first few days, the beauty of the city cast a spell over us, but after a time the difficulty of getting around all the irregularly cobbled one-way streets on our "moto" began wear on us. We even noticed feeling claustrophobic in the labyrinth of narrow, traffic-congested streets and occasionally got the creeps from the ostentatious wealth of our countrymen in a place where so many people live in poverty. One unfortunate consequence of this influx of North Americans is that housing prices near the centro have been driven so high that few Mexicans can afford to live there anymore.

So to San Miguel de Allende (Population 65,000, Elevation 6,100 ft) we went, another lovely hillside colonial town, but with the difference of also being home to some 7,000 at least part-time expatriated gringos, or about 10% of the population, mostly seniors, not counting the additional tourists like us. A very few are assimilated into the Mexican culture, but most are isolated in luxury houses and many speak very little Spanish beyond what's required to do their shopping and give directions to gardeners, maids and other workers. On our visit to the cemetery (we often visit Mexican cemeteries), we even discovered a separate section reserved for Americans, gated off from the main area. For the first few days, the beauty of the city cast a spell over us, but after a time the difficulty of getting around all the irregularly cobbled one-way streets on our "moto" began wear on us. We even noticed feeling claustrophobic in the labyrinth of narrow, traffic-congested streets and occasionally got the creeps from the ostentatious wealth of our countrymen in a place where so many people live in poverty. One unfortunate consequence of this influx of North Americans is that housing prices near the centro have been driven so high that few Mexicans can afford to live there anymore.

|

|

|---|

As promised, though, San Miguel de Allende had plenty of language schools to choose from, so we chose the one closest to our camp, the beautiful Instituto Allende, primarily a fine arts institute which also offers language classes and private instruction. We signed up for two weeks, 4 hours a day, Kathleen in private lessons held under an umbrella in the garden, plus an hour of conversation, and Rus in group for grammar and conversation. Believe us, that was plenty! At the end, we felt wrung out and hung up to dry, needing time to assimilate all we'd been taught. Did you know that in addition to the present tense, the Spanish language has 13 other tenses including 4 past, 4 subjunctive, 2 future, 2 conditional, and that people actually use them? Not only that, but getting into the complex usage of personal and impersonal pronouns is like diving into shark-infested waters. People who say Spanish is easy have never conjugated an irregular reflexive verb in the preterito, second person familiar! But at least now we know what we're up against. That said, "vale la pena", it's worth the pain, for we noticed that we were now having conversations AND understanding at a new level far from where we began. We can now talk about politics, ideas, and even feelings, (not easily, and it's not pretty, but we can!!) and our immersion into local experience has increased significantly. We highly recommend Spanish classes to all travelers in Latin America. Plus they provide a wonderful opportunity to dive more intimately into the lives and the culture of the local community.

As promised, though, San Miguel de Allende had plenty of language schools to choose from, so we chose the one closest to our camp, the beautiful Instituto Allende, primarily a fine arts institute which also offers language classes and private instruction. We signed up for two weeks, 4 hours a day, Kathleen in private lessons held under an umbrella in the garden, plus an hour of conversation, and Rus in group for grammar and conversation. Believe us, that was plenty! At the end, we felt wrung out and hung up to dry, needing time to assimilate all we'd been taught. Did you know that in addition to the present tense, the Spanish language has 13 other tenses including 4 past, 4 subjunctive, 2 future, 2 conditional, and that people actually use them? Not only that, but getting into the complex usage of personal and impersonal pronouns is like diving into shark-infested waters. People who say Spanish is easy have never conjugated an irregular reflexive verb in the preterito, second person familiar! But at least now we know what we're up against. That said, "vale la pena", it's worth the pain, for we noticed that we were now having conversations AND understanding at a new level far from where we began. We can now talk about politics, ideas, and even feelings, (not easily, and it's not pretty, but we can!!) and our immersion into local experience has increased significantly. We highly recommend Spanish classes to all travelers in Latin America. Plus they provide a wonderful opportunity to dive more intimately into the lives and the culture of the local community.

|

|

|---|

A hidden advantage of language schools is the opportunity to make friends, both with the teachers (who you get to know quite well in private lessons) and with other students, who are struggling along beside you to find the right words and to integrate it all. It is a bonding experience. Perhaps these personal connections we made will be what we remember most about San Miguel. That and, we hope, the Spanish.

A hidden advantage of language schools is the opportunity to make friends, both with the teachers (who you get to know quite well in private lessons) and with other students, who are struggling along beside you to find the right words and to integrate it all. It is a bonding experience. Perhaps these personal connections we made will be what we remember most about San Miguel. That and, we hope, the Spanish.

Photos: Kathleen and Barbara (left) and our faithful camp neighbors at La Siesta, Duncan, Lisa, and Devon (above, right), with Katie pictured further right.

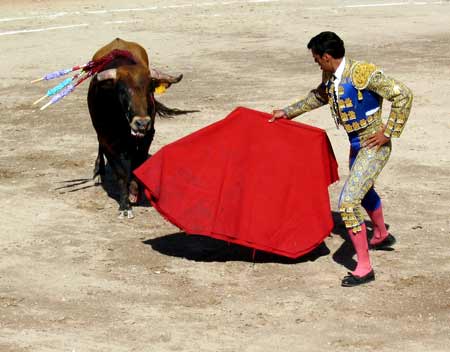

One of our last acts in San Miguel de Allende was to go to a Corrida de Toros (bullfight) with Mel and Barbara, friends from school. It's Mexico, right? It's good to experience the culture in all different ways, or so we thought. Well, we have never seen such a display of cruelty, torture, and inept butchery in our lives. Being a small city, San Miguel's plaza de toros is quite small, and we foolishly chose to sit in the front row, so that the bull was often only a few feet away from us. It was no longer bull-fight season so these were "minor-league" matadors who were gaining experience. The plaza was largely empty and the audience was so scattered that the vital group energy that is such a part of the tradition never developed. We were way too close for any ritual and pageantry to outweigh the blood, shit, saliva and bellows of the terrified bull as he tried alternately to defend himself and escape his tormentors. If you've ever been to a bullfight, you know how it goes; if you haven't, we won't go into it here. Suffice to say, after being run around the ring for 45 minutes, speared, jabbed, harassed and manipulated, and after 4 failed "estocadas" (killing thrusts) from the matador, the exhausted bull could run no more. He just stood there facing his costumed assassins, heaving and bellowing. Finally, from exhaustion and loss of blood, the bull's legs collapsed under him, and one of them sneaked up behind with a sword thrust to the back of his head, which killed him. The matador bowed, the crowd applauded, Rus booed, Kathleen cried, the band struck up a tune, and a shiny SUV drove out to the ring and dragged the dead bull out by its hind legs, the first of six to entertain the crowd that afternoon. But one was enough for us; we left, sickened and disgusted, wondering what had we been thinking to go, and what were the deeper implications for a culture that considers that entertainment?

One of our last acts in San Miguel de Allende was to go to a Corrida de Toros (bullfight) with Mel and Barbara, friends from school. It's Mexico, right? It's good to experience the culture in all different ways, or so we thought. Well, we have never seen such a display of cruelty, torture, and inept butchery in our lives. Being a small city, San Miguel's plaza de toros is quite small, and we foolishly chose to sit in the front row, so that the bull was often only a few feet away from us. It was no longer bull-fight season so these were "minor-league" matadors who were gaining experience. The plaza was largely empty and the audience was so scattered that the vital group energy that is such a part of the tradition never developed. We were way too close for any ritual and pageantry to outweigh the blood, shit, saliva and bellows of the terrified bull as he tried alternately to defend himself and escape his tormentors. If you've ever been to a bullfight, you know how it goes; if you haven't, we won't go into it here. Suffice to say, after being run around the ring for 45 minutes, speared, jabbed, harassed and manipulated, and after 4 failed "estocadas" (killing thrusts) from the matador, the exhausted bull could run no more. He just stood there facing his costumed assassins, heaving and bellowing. Finally, from exhaustion and loss of blood, the bull's legs collapsed under him, and one of them sneaked up behind with a sword thrust to the back of his head, which killed him. The matador bowed, the crowd applauded, Rus booed, Kathleen cried, the band struck up a tune, and a shiny SUV drove out to the ring and dragged the dead bull out by its hind legs, the first of six to entertain the crowd that afternoon. But one was enough for us; we left, sickened and disgusted, wondering what had we been thinking to go, and what were the deeper implications for a culture that considers that entertainment?

But we have to remember, we're in their country, not ours, and we have no cultural or historical context to fit a bullfight into. Even so, we don't have to like it, any more than we have to like the nightly hours-long fusillade of fireworks. When do people sleep here, and where do they get these industrial explosives-grade fireworks? Well, we found out that they are used to announce fiestas, Saint's Days, and like a church bell, as a call to service. In Mexico there are fiestas for some saint or other several times a week so the thunder of fireworks is an ongoing irritant until you get tired enough or are here long enough to sleep through the racket. The fireworks are made by hand using pieces of bamboo packed with black powder and a fuse. Four men were killed in San Miguel a few years ago in a fireworks accident, and the city considered implementing controls but public outcry was so strong, they dropped the idea.

But we have to remember, we're in their country, not ours, and we have no cultural or historical context to fit a bullfight into. Even so, we don't have to like it, any more than we have to like the nightly hours-long fusillade of fireworks. When do people sleep here, and where do they get these industrial explosives-grade fireworks? Well, we found out that they are used to announce fiestas, Saint's Days, and like a church bell, as a call to service. In Mexico there are fiestas for some saint or other several times a week so the thunder of fireworks is an ongoing irritant until you get tired enough or are here long enough to sleep through the racket. The fireworks are made by hand using pieces of bamboo packed with black powder and a fuse. Four men were killed in San Miguel a few years ago in a fireworks accident, and the city considered implementing controls but public outcry was so strong, they dropped the idea.

Photo: Houses in morning are marked with a black ribbons

Below, Duncan rides the "moto"

To Patzcuaro

Saying goodbye to our home and neighbors of more than 2 weeks (amazing how easy it is to become attached!) and to the friends and memories we made in San Miguel, we moved on. Rus was sick of touristy colonial cities and since Kathleen had already visited Guanajuato years ago, she was willing to skip this beautiful UNESCO world heritage site in favor of family harmony. We chose Patzcuaro as our destination for the day. It sure felt good to be on the road again. Heading south through Mexico's increasingly beautiful colonial highlands, dotted with lakes and grasslands. We detoured a bit to visit our first ruins, the ancient city of Tzintzuntzan (that's right, 3 each t's, z's, and n's!), the 15th century Tarascan capital of what is now the state of Michoacan as well as parts of Jalisco and Colima, and once home to 40,000 people. The partly restored ceremonial temples are all that is left of this once great city, they are perched advantageously on a hill overlooking the lake, while the the people apparently lived on and farmed the lands below. Being from a small California town of some 16,000, the scale of these ancient cities boggles our minds. Rus felt like a country bumpkin walking around these huge plazas and temple platforms, imagining the sophistication required to build and administer something on this scale at that time, without metal tools, the wheel, or even answering machines!

Saying goodbye to our home and neighbors of more than 2 weeks (amazing how easy it is to become attached!) and to the friends and memories we made in San Miguel, we moved on. Rus was sick of touristy colonial cities and since Kathleen had already visited Guanajuato years ago, she was willing to skip this beautiful UNESCO world heritage site in favor of family harmony. We chose Patzcuaro as our destination for the day. It sure felt good to be on the road again. Heading south through Mexico's increasingly beautiful colonial highlands, dotted with lakes and grasslands. We detoured a bit to visit our first ruins, the ancient city of Tzintzuntzan (that's right, 3 each t's, z's, and n's!), the 15th century Tarascan capital of what is now the state of Michoacan as well as parts of Jalisco and Colima, and once home to 40,000 people. The partly restored ceremonial temples are all that is left of this once great city, they are perched advantageously on a hill overlooking the lake, while the the people apparently lived on and farmed the lands below. Being from a small California town of some 16,000, the scale of these ancient cities boggles our minds. Rus felt like a country bumpkin walking around these huge plazas and temple platforms, imagining the sophistication required to build and administer something on this scale at that time, without metal tools, the wheel, or even answering machines!

|

|

|---|

We landed in the town of Patzcuaro that evening with time to set up camp, write a few e-mails and take an evening stroll. Patzcuaro is a lakeside town, a plus for Ziggy, who entertained a few onlookers with her usual repertoire of stick retrieves in the murky water just as darkness fell. We think it's the most beautiful of Mexico's colonial era cities we've seen, with its ancient cathedrals, spacious central zocalos, Spanish-style arcaded buildings, and a colorful, sprawling market where we noticed items so mysterious that knowing their names wouldn't have helped in the least (we found out later some were large roasted ants!). It appeared as if the city center had been designed by a single architect, built over a 20-year period in the late 1500's, and then left as-is. We had an entertaining few hours the next morning, poking around the cobbled streets on our "moto", buying delicious but unidentifiable food items in the mercado (an unknown fruit and a sort of cornmeal dumpling with heavy cream and green salsa on top), then eating them in the zocalo, surrounded by the bustle of

We landed in the town of Patzcuaro that evening with time to set up camp, write a few e-mails and take an evening stroll. Patzcuaro is a lakeside town, a plus for Ziggy, who entertained a few onlookers with her usual repertoire of stick retrieves in the murky water just as darkness fell. We think it's the most beautiful of Mexico's colonial era cities we've seen, with its ancient cathedrals, spacious central zocalos, Spanish-style arcaded buildings, and a colorful, sprawling market where we noticed items so mysterious that knowing their names wouldn't have helped in the least (we found out later some were large roasted ants!). It appeared as if the city center had been designed by a single architect, built over a 20-year period in the late 1500's, and then left as-is. We had an entertaining few hours the next morning, poking around the cobbled streets on our "moto", buying delicious but unidentifiable food items in the mercado (an unknown fruit and a sort of cornmeal dumpling with heavy cream and green salsa on top), then eating them in the zocalo, surrounded by the bustle of  market day. This was the first place we've visited to show a strong Indian influence. Maybe it was because we were in such a good mood but people seemed exceptionally friendly and we had lots of fun little exchanges. We stayed at the Villa Patzcuaro, an immaculate little hotel with lovely gardens, a small pool and 10 or so spaces for campers in a grassy field behind the buildings. It offered utilities, bathrooms (cold showers), and even a kitchen! In this kitchen was a tiny stack of books travelers had left, with the custom to leave a book if you take one. As he browsed through the pile of maybe 8-10 books, Rus was astounded to come across the book, Driving Packet for Central & South America, by the South American Explorers, a country-by-country reference of maps, travel tips and road

market day. This was the first place we've visited to show a strong Indian influence. Maybe it was because we were in such a good mood but people seemed exceptionally friendly and we had lots of fun little exchanges. We stayed at the Villa Patzcuaro, an immaculate little hotel with lovely gardens, a small pool and 10 or so spaces for campers in a grassy field behind the buildings. It offered utilities, bathrooms (cold showers), and even a kitchen! In this kitchen was a tiny stack of books travelers had left, with the custom to leave a book if you take one. As he browsed through the pile of maybe 8-10 books, Rus was astounded to come across the book, Driving Packet for Central & South America, by the South American Explorers, a country-by-country reference of maps, travel tips and road  conditions, entry and exit regulations, etc., a gold mine of information. For example, it contains the names and contact information for 17 shipping companies to help get our rig from Central to South America. We'd heard of this book, but had no idea where to find one; Rus quickly traded a really good book for it, and occasionally takes it out to make sure he wasn't dreaming the whole thing.

conditions, entry and exit regulations, etc., a gold mine of information. For example, it contains the names and contact information for 17 shipping companies to help get our rig from Central to South America. We'd heard of this book, but had no idea where to find one; Rus quickly traded a really good book for it, and occasionally takes it out to make sure he wasn't dreaming the whole thing.

Kathleen was delighted to find that the colorful Mexican tablecloths she'd been wanting to find are made in the area. She bought several because, as someone enchanted with the vibrant use of color here, choosing only one was impossible. Our stay in Patzcuaro was short but rich and will definitely return someday.

|

|

|---|

Brick sellers rest in the shade of their trucks until customers arrive

Paracho and more ruins

Leaving Patzcuaro, we took another detour to the famous (if you play guitar) town of Paracho, where it seems just about everyone makes guitars and other fretted instruments. Rus had always wanted to visit, though Kathleen had been there some 35 years before with her first husband (also a guitar player!). The quality of a good majority of the instruments we saw in the shops was pretty bad, as if they'd been made as souvenirs rather than to be played. But we found a luthiers' exposition, where the better instruments of many of the local builders were submitted, and saw some fine guitars there. Rus was interested in one, but the staff couldn't find the price, so we left without it, sort of relieved not to have the burden of an additional material object to deal with.

Leaving Patzcuaro, we took another detour to the famous (if you play guitar) town of Paracho, where it seems just about everyone makes guitars and other fretted instruments. Rus had always wanted to visit, though Kathleen had been there some 35 years before with her first husband (also a guitar player!). The quality of a good majority of the instruments we saw in the shops was pretty bad, as if they'd been made as souvenirs rather than to be played. But we found a luthiers' exposition, where the better instruments of many of the local builders were submitted, and saw some fine guitars there. Rus was interested in one, but the staff couldn't find the price, so we left without it, sort of relieved not to have the burden of an additional material object to deal with.

We'd always wondered how it came to be that so many towns  in this part of Mexico specialize in the manufacture of one type of product that the town is known for, be it guitars, furniture, glass-blowing or whatever. Here's how it happened: the 16th century Bishop Vasco de Quiroga, a rare advocate for the indigenous peoples, undertook to teach them different trades and manufacturing skills to make each village self-sufficient under colonial rule and much of his legacy survives today. He's still revered all over Michoacan, and we like him, too, a dramatic departure from 95% of his colleagues.

in this part of Mexico specialize in the manufacture of one type of product that the town is known for, be it guitars, furniture, glass-blowing or whatever. Here's how it happened: the 16th century Bishop Vasco de Quiroga, a rare advocate for the indigenous peoples, undertook to teach them different trades and manufacturing skills to make each village self-sufficient under colonial rule and much of his legacy survives today. He's still revered all over Michoacan, and we like him, too, a dramatic departure from 95% of his colleagues.

Photo:

A shady spot in Tingambato

It's hard to drive right past a ruins, even if it's not a famous one. This seemed a good day to see more ruins so we detoured through the village of Tingambato, holding our breath to see if we could squeeze through the narrow streets to reach Tinganio on the outskirts of town. Tinganio was a pre-Tascaran city thriving between 450-900 AD. Who lived there is a mystery but evidence suggests they were related to tribes in Equador. We happened to be the only visitors there and enjoyed a nice talk with the caretaker (in Spanish!) about pre-Columbian history and contemporary Mexican politics which we are eager to learn more about.

|

|

|---|

A Volcano and an Indigenous Village

We'd planned to reach the coast north of Zihuatanejo by evening, but we had "squandered" that opportunity by spending so long in Patzcuaro, the ruins and then Paracho. We needed a place to camp and read about one not far off near a volcano. Sounded interesting. So we ducked off the highway and wound through the mountains to the village of Angahuan, where we were met by Lazaro and his horse, who escorted us through a maze of narrow cobbled and dirt streets to a beautiful camping spot in a wooded park. We'd have never made it without Lazaro, as the main streets through town were blocked to vehicles by low-hanging tarps covering vendors's stalls for market day.

We'd planned to reach the coast north of Zihuatanejo by evening, but we had "squandered" that opportunity by spending so long in Patzcuaro, the ruins and then Paracho. We needed a place to camp and read about one not far off near a volcano. Sounded interesting. So we ducked off the highway and wound through the mountains to the village of Angahuan, where we were met by Lazaro and his horse, who escorted us through a maze of narrow cobbled and dirt streets to a beautiful camping spot in a wooded park. We'd have never made it without Lazaro, as the main streets through town were blocked to vehicles by low-hanging tarps covering vendors's stalls for market day.

Our camp at Centro Turistico overlooked a large lava-covered valley and the famous Volcan Paricutin, which first erupted in 1943 under the feet of a farmer tilling his field (who lived to tell the tale), and covered thousands of hectares of farmland and two entire towns by the time it was done, nine years later. It wasn't hard for Lazaro to talk us into a trip on horseback to see the crater up close and arrangements were made to leave early in the morning. After making dinner, we heard a recorded voice, a woman's, chanting from a loudspeaker in town a few hundred yards up the road. We decided to investigate. The town of Angahuan has a totally indigenous population, where Spanish is spoken only to outsiders. The people speak Purepecha and have lived in and tilled these hillsides for generations in relative isolation until the eruption, which brought people here from all over the world. The women wear their traditional dress: colorful satin pleated blouses, contrasting colorful satin pleated skirts with full-length velvet aprons, of different colors still, often bordered with lace. Many had babies strapped to their backs or shawls wrapped around their heads.

Our camp at Centro Turistico overlooked a large lava-covered valley and the famous Volcan Paricutin, which first erupted in 1943 under the feet of a farmer tilling his field (who lived to tell the tale), and covered thousands of hectares of farmland and two entire towns by the time it was done, nine years later. It wasn't hard for Lazaro to talk us into a trip on horseback to see the crater up close and arrangements were made to leave early in the morning. After making dinner, we heard a recorded voice, a woman's, chanting from a loudspeaker in town a few hundred yards up the road. We decided to investigate. The town of Angahuan has a totally indigenous population, where Spanish is spoken only to outsiders. The people speak Purepecha and have lived in and tilled these hillsides for generations in relative isolation until the eruption, which brought people here from all over the world. The women wear their traditional dress: colorful satin pleated blouses, contrasting colorful satin pleated skirts with full-length velvet aprons, of different colors still, often bordered with lace. Many had babies strapped to their backs or shawls wrapped around their heads.

As we walked in the darkness through the narrow streets of Angahuan listening to the chanting voice we realized we had entered another world. Small, simple homes lined each side of the dirt or cobbled streets, the light inside them calling our attention to women flipping tortillas over over small fires in the bare rooms, smoke pouring out the open doors and windows, girls stirring pots of something, toddlers playing in the doorways, kids kicking balls in the street. Dogs, lots of dogs. And still, the chanting continued. Some men were still at work, making pine avocado crates in their open air shops, taking advantage of the cool evening air. People of all ages gathered in small groups on the street or strolled together, women carrying bundles on their heads. Passing in the dark we were hardly noticed. It felt good to be almost invisible, to have an intimate view of their world without disturbing it. The chanting changed direction and got softer, a mysterious backdrop that kept us wondering, "What is she saying?", "and why is she saying it?" and "What does it mean to them?" We followed the voice and finally located the source, 3 loudspeakers mounted high on poles to broadcast to the entire village. The chanting, which had a cadence somewhat like Sanskrit, lasted for nearly an hour. We guessed it had some religious significance, a sort of prayer, although we'll never know for sure. But both of us were exhilarated by the magic of the night and this intriguing town we'd stumbled upon.

Bright and early at 7:00 the next morning we were met by Lazaro, whose job had been to arrange for the horses, and Felipe, our actual guide. Ziggy accompanied us on foot, though she wanted out of the whole deal when she discovered that we were accompanied by a small herd of cantankerous Mexican cattle for the first little ways. The trail led through forest, then farmland, then avocado orchards, then onto the lava fields, where we were thankful to have gotten off to an early start, as the sun's heat was radiating up from the black lava below as well as beating down from above. It had been 54 years since the last eruption, but the closer we got, the less

Bright and early at 7:00 the next morning we were met by Lazaro, whose job had been to arrange for the horses, and Felipe, our actual guide. Ziggy accompanied us on foot, though she wanted out of the whole deal when she discovered that we were accompanied by a small herd of cantankerous Mexican cattle for the first little ways. The trail led through forest, then farmland, then avocado orchards, then onto the lava fields, where we were thankful to have gotten off to an early start, as the sun's heat was radiating up from the black lava below as well as beating down from above. It had been 54 years since the last eruption, but the closer we got, the less  time it seemed. After riding for 2 1/2 hours, we dismounted at the foot of the volcano, left the horses tied under a pine tree, and began an arduous trek up to the rim of the crater, winding among dozens of vents breathing steam into the cooler (relatively) late morning air. Finally reaching the top, we got a good look at the extent of the eruptions over that nine-year period. Frozen rivers of lava stretched out for miles in several directions; in places where only ash had covered the soil, avocado trees were enjoying the benefits; in places where there had been towns, only mountains of jagged lava stood, with the single exception of a stone tower of a 17th century church, rising miraculously out of the lava, an unreal sight. Not one person died in the eruptions, but thousands of people were evacuated and relocated to distant areas.

time it seemed. After riding for 2 1/2 hours, we dismounted at the foot of the volcano, left the horses tied under a pine tree, and began an arduous trek up to the rim of the crater, winding among dozens of vents breathing steam into the cooler (relatively) late morning air. Finally reaching the top, we got a good look at the extent of the eruptions over that nine-year period. Frozen rivers of lava stretched out for miles in several directions; in places where only ash had covered the soil, avocado trees were enjoying the benefits; in places where there had been towns, only mountains of jagged lava stood, with the single exception of a stone tower of a 17th century church, rising miraculously out of the lava, an unreal sight. Not one person died in the eruptions, but thousands of people were evacuated and relocated to distant areas.

On the return trip, having gotten more familiar with our guide Felipe, a gentle and quiet Purepecha Indian man of about 45 who'd lived his whole life in Angahuan, we asked him about the chanting from the night before, and Felipe replied that it was played three times daily, at mealtimes, announcing that it was time to eat. Skeptical (and a bit nosey), Rus replied that it seemed like a lot of fuss just to tell people it was time to eat, and did it maybe have some religious significance?, but Felipe stuck to his story, (and we'll stick to ours).

|

|

|---|

Back on the horses and about 20 kilometers later, we arrived at our camp, our butts as sore as Ziggy's paws, glad to disengage from those handmade wooden saddles. From our camp, we looked off in the distance to the volcano we'd just climbed a few hours before, and the church tower poking through the lava, amazed that we'd gone that far and back in only 7 hours. Relaxing before dinner, Rus looked at the calendar and was surprised to discover that it was May 24, his birthday! He had a couple of beers to celebrate, and at his request Kathleen made a salad for dinner, a real one, with lettuce. Life is getting a little simpler.

|

valuable information). This RV park, the Mar Rosa, was right on the beach on the north side of town, we found it to be very pleasant, clean, and well-run and because it is no longer tourist season, there were only 3 or 4 other campers there. The heat and humidity made us lazy and it was so comfortable under the big shade trees that we just hung out there and relaxed, visited with neighbors and took wonderful evening beach walks. Other times we'd catch an open air taxi to the old part of town where we explored the market, the malecon and plazas, and walked for miles and miles.

valuable information). This RV park, the Mar Rosa, was right on the beach on the north side of town, we found it to be very pleasant, clean, and well-run and because it is no longer tourist season, there were only 3 or 4 other campers there. The heat and humidity made us lazy and it was so comfortable under the big shade trees that we just hung out there and relaxed, visited with neighbors and took wonderful evening beach walks. Other times we'd catch an open air taxi to the old part of town where we explored the market, the malecon and plazas, and walked for miles and miles.