Travel Log, Recent Entries

GUATEMALA!

The Border Crossing

We arrived at last at the border town of La Mesilla, to a scene that can only be described as pandemonium. It was market day, and it was raining, goods from stalls on both sides spilling out into the street, people covering their wares with tarps, runoff from one pouring onto another and out onto the crowds making their way between the and vendors and the jammed traffic, money changers with thick wads of bills changing pesos to quetzals, dollars to pesos, quetzals to pesos, whatever you wanted at an exchange rate to be negotiated, boys offering to help you cross, fee to be negotiated, and uncertain customs and immigration signage. We pulled over and parked on the street across from the line of offices. Since we didn't want to leave our rig in such a chaotic place, Kathleen left with our documents to do the paperwork while Rus and Ziggy stayed behind. Fortunately, it stopped raining, so he was able to get outside and take some photos. Our rig immediately became the new center for the money changers; maybe they liked to gather near something visible. Rus chatted with them but passed up the first offer of an exchange rate, waited until 5 of them were together, then asked the group for the best rate. He had no idea what a quetzal was worth, but it was a much better offer! We arrived at last at the border town of La Mesilla, to a scene that can only be described as pandemonium. It was market day, and it was raining, goods from stalls on both sides spilling out into the street, people covering their wares with tarps, runoff from one pouring onto another and out onto the crowds making their way between the and vendors and the jammed traffic, money changers with thick wads of bills changing pesos to quetzals, dollars to pesos, quetzals to pesos, whatever you wanted at an exchange rate to be negotiated, boys offering to help you cross, fee to be negotiated, and uncertain customs and immigration signage. We pulled over and parked on the street across from the line of offices. Since we didn't want to leave our rig in such a chaotic place, Kathleen left with our documents to do the paperwork while Rus and Ziggy stayed behind. Fortunately, it stopped raining, so he was able to get outside and take some photos. Our rig immediately became the new center for the money changers; maybe they liked to gather near something visible. Rus chatted with them but passed up the first offer of an exchange rate, waited until 5 of them were together, then asked the group for the best rate. He had no idea what a quetzal was worth, but it was a much better offer!

Entering Guatemala

Meanwhile Kathleen whizzed through the border hoops, as all the Guatemalan officials were more interested in the world cup soccer playoffs on TV than in our crossing. By "whizzed", we mean it only took about an hour, and we were on our way. Our tires were sprayed before we even got out of the truck for a fee of around $8, passports stamped at “Migration” (no fee), and last but taking longest, were the vehicle permits at “Aduana”. The fee for both Turtle and the moto was about $10, paid in Quetzals at the bank next door. After all the  hours spent in careful preparation of Ziggy's papers, including a Mexican vet's certification, no one was interested in the fact that we were bringing a Labrador Retriever into Guatemala. The official said, "Just one dog, no problema", and waved us through. Kathleen asked 3 different officials and got the same response, she just hoped this wouldn't haunt us later. We've heard plenty of bad stories about lengthly, difficult crossings, complications, corrupt officials, inconsistent policies, etc, and maybe we'll get those later. We don't doubt they're true, but we've yet to meet a border official who wasn't at least courteous, some more than others. And besides, an inconsistent policy can be perfectly ok if it works in your favor! hours spent in careful preparation of Ziggy's papers, including a Mexican vet's certification, no one was interested in the fact that we were bringing a Labrador Retriever into Guatemala. The official said, "Just one dog, no problema", and waved us through. Kathleen asked 3 different officials and got the same response, she just hoped this wouldn't haunt us later. We've heard plenty of bad stories about lengthly, difficult crossings, complications, corrupt officials, inconsistent policies, etc, and maybe we'll get those later. We don't doubt they're true, but we've yet to meet a border official who wasn't at least courteous, some more than others. And besides, an inconsistent policy can be perfectly ok if it works in your favor!

Our toughest negotiation was still ahead, to make it through the rest of these crazy streets on market day. The chaos and congestion was unimaginable, and we burst out laughing that here we were, in the thick of it. It was great entertainment, and it's wonderful to see how understanding and cooperative everyone is in a jam like this. People will move for you, get out and help you inch past their vehicle, or you'll do it for them, mirrors tucked in on both sides. The streets in many of the older towns in Latin America were designed for foot, horse and carriage traffic, not cars, trucks and busses, and certainly not the volume that the 20th  century brought to this part of the world. It's an impossible situation, but people have adapted to it, and somehow it works. Soon enough, the town of La Mesilla released us from its grasp and nudged us out onto the highway. We made for the town of Huehuetenango, where we'd heard of a hotel that offered spaces for rvs. We hired a cab to lead us there, worth every quetzal, and sure enough they had a field in back for us to park, even an electrical feed, and it was 80 quetzals, about half again the cost of one of their rooms! This was robbery and we knew it, but it was late and it had been a long day. We forked it over, ate a bad meal in their restaurant, went back to our rig and slept through an all-night rain. We later discovered that the meal we'd eaten wasn't in fact bad; just typical Guatemalan meat, beans and rice. century brought to this part of the world. It's an impossible situation, but people have adapted to it, and somehow it works. Soon enough, the town of La Mesilla released us from its grasp and nudged us out onto the highway. We made for the town of Huehuetenango, where we'd heard of a hotel that offered spaces for rvs. We hired a cab to lead us there, worth every quetzal, and sure enough they had a field in back for us to park, even an electrical feed, and it was 80 quetzals, about half again the cost of one of their rooms! This was robbery and we knew it, but it was late and it had been a long day. We forked it over, ate a bad meal in their restaurant, went back to our rig and slept through an all-night rain. We later discovered that the meal we'd eaten wasn't in fact bad; just typical Guatemalan meat, beans and rice.

In the morning we used one of the rooms to shower, and made our way through the labyrinth of Huehuetenango, finally arriving downtown in blocked traffic, ahead some kind of Saturday morning parade with a multi-car police escort. As it drew closer, we saw that it was a Domino's Pizza parade, led by marching bands and dancers from the local schools bearing Domino's banners, the fleet of pizza delivery motorcycles in formation, bringing up the rear. The noise from the music was deafening. Everyone was having a great time, from the police to the marching bands to the people stuck in traffic. Certain U.S. companies seem to have done well in Latin America, among them Office Depot, Blockbuster Video, and just about every major fast food chain. As much as we dislike most chains, we have to acknowledge the efforts these companies have made to do business in another culture, and it seems to have paid off for them. Guatemalans love parades and take every opportunity to celebrate, even for Domino's Pizza.

Eventually Huehuetenango spit us out the other side onto the highway, and we made for Lago Atitlan, the famous lake in the south bordered by three gorgeous green volcanoes on one side, mountains and waterfalls on all the others. Arriving at Solola (accent on the "a", which we don't know how to do on an English keyboard), we squeezed our way through traffic to the bus terminal, which dominates one side of the town square, opposite the market. It makes sense to put the terminal where people want to arrive and depart, but boy does it create congestion in these small towns! Amazingly we found a parking place right on the plaza among the busses, then made our way to the market to get lunch from the vendors and poke around a bit before we headed to Panajachel, our destination. The region around Solola is famous for its weaving, and this market was our first introduction to the amazing skill and prolific production of the indigenous women here. It also must be the copal capitol of Guatemala, as we saw more of it in more forms than we've ever seen, from pure resin nuggets, to granules, to cakes in various shapes and sizes, wrapped in tight bundles of dried leaves. We wanted to bring some home to our friends, many of whom use incense and would love to have copal, but we figured if there was this much here, it must be everywhere. It isn't.

Panajachel on Lago Atitlan

Continuing down the steep winding road to Panajachel we dropped below the fog layer and caught our first view of Lake Atitlan far below, reflecting the overcast sky in silver, on the opposite shore three perfect volcanoes rising into the clouds. It was one of those moments nothing can prepare you for; your ability to take it in is overwhelmed, you are simply transported to another reality where scenes like this exist. Along the way waterfalls cascade hundreds of feet off the sheer cliffs, vehicles threaten to do the same, and eventually both arrive at the lake seeking their lowest level. We found a perfect camp in a field next to the Hotel Tzanjuyu, a once-lavish lakeside resort, now vacant with two old gentlemen as caretakers and a guardian in a trailer opposite our field. From our camp we had access to the hotel pools just a few feet away, a huge tiled patio, bathrooms with showers, electricity, and a sewage dump. This in addition to our own private view of Lake Atitlan and the aforementioned volcanoes. And as if that weren't enough, there was another camper there, with California plates! Continuing down the steep winding road to Panajachel we dropped below the fog layer and caught our first view of Lake Atitlan far below, reflecting the overcast sky in silver, on the opposite shore three perfect volcanoes rising into the clouds. It was one of those moments nothing can prepare you for; your ability to take it in is overwhelmed, you are simply transported to another reality where scenes like this exist. Along the way waterfalls cascade hundreds of feet off the sheer cliffs, vehicles threaten to do the same, and eventually both arrive at the lake seeking their lowest level. We found a perfect camp in a field next to the Hotel Tzanjuyu, a once-lavish lakeside resort, now vacant with two old gentlemen as caretakers and a guardian in a trailer opposite our field. From our camp we had access to the hotel pools just a few feet away, a huge tiled patio, bathrooms with showers, electricity, and a sewage dump. This in addition to our own private view of Lake Atitlan and the aforementioned volcanoes. And as if that weren't enough, there was another camper there, with California plates!

Our neighbors were Mark and Liesbet, from California and Belgium, who are on an open-ended journey exploring Central America with their two dogs. They are younger professional people who left everything behind to see what else opened up. Their story is a long and interesting one: they'd originally bought a sailboat to make this journey. After months and many dollars outfitting the boat, they set sail from California, only to discover their dogs were freaking out, and hated it! You have to be a dog lover to understand how it made perfect sense to sell the boat, buy a truck with a camper, and press on. We've met several younger people, even some families, on our trip so far who have left it all behind, taken leaves of absence or outright quit their jobs and sold their homes, and taken to the road. It's not a vacation, they're quick to tell you (and so are we), it's a life change, with all that entails. Even if you return eventually to the same place, you're not the same person. Our neighbors were Mark and Liesbet, from California and Belgium, who are on an open-ended journey exploring Central America with their two dogs. They are younger professional people who left everything behind to see what else opened up. Their story is a long and interesting one: they'd originally bought a sailboat to make this journey. After months and many dollars outfitting the boat, they set sail from California, only to discover their dogs were freaking out, and hated it! You have to be a dog lover to understand how it made perfect sense to sell the boat, buy a truck with a camper, and press on. We've met several younger people, even some families, on our trip so far who have left it all behind, taken leaves of absence or outright quit their jobs and sold their homes, and taken to the road. It's not a vacation, they're quick to tell you (and so are we), it's a life change, with all that entails. Even if you return eventually to the same place, you're not the same person.

Panajachel is the main tourist destination on Lake Atitlan, and has been so since the 1970's, when it was an outpost of expatriated counter-culture youth (ok, hippies), who mostly ducked out when the bad trouble began in Guatemala in the early '80's, and we don't blame them. Some have returned, others followed, and still many more temporarily flock to Panajachel on a daily basis. We were there about the time of summer break, and the streets were filled with young college students passing through, taking Spanish lessons or volunteering with community projects in the area. After being the only Americans in many of the places we've stayed, it's still a surprise to see so many of our countrymen the further we get from our country! But in our outpost on the lakeshore with Mark and Liesbet, Panajachel seemed far away, unless we went in for the market, the internet cafe, or for Rus, the worst haircut in Guatemala! Panajachel is the main tourist destination on Lake Atitlan, and has been so since the 1970's, when it was an outpost of expatriated counter-culture youth (ok, hippies), who mostly ducked out when the bad trouble began in Guatemala in the early '80's, and we don't blame them. Some have returned, others followed, and still many more temporarily flock to Panajachel on a daily basis. We were there about the time of summer break, and the streets were filled with young college students passing through, taking Spanish lessons or volunteering with community projects in the area. After being the only Americans in many of the places we've stayed, it's still a surprise to see so many of our countrymen the further we get from our country! But in our outpost on the lakeshore with Mark and Liesbet, Panajachel seemed far away, unless we went in for the market, the internet cafe, or for Rus, the worst haircut in Guatemala!

Santiago Atitlan

There's a good-sized town on the other side of the lake called Santiago Atitlan . It's tucked into a cove so you can't see it from Panajachel, but it's the largest and least touristy of the main lakeside towns, so we went across to see it. Lake Atitlan is ringed with towns, villages, settlements and farms, and there's a lively ferry commerce in getting people from one place to another, as people may work in one town and live in another. The road, if it's not washed out, would take hours, but it only takes about half an hour to cross by boat, and it's a lot safer. Kathleen wanted to see Santiago because it's one of the abodes of the famed Maximon, patron saint of overindulgence, said to be a blend of San Simon, Pedro Alvarado, one of Cortez's most ruthless officers, and a Mayan deity. A life-sized wooden effigy of Maximon resides in a different home each year in Sanitiago, and worshipers (and tourists like us) are invited to make offerings of money, tobacco, and booze in return for miracles, blessings or photographs. There's a good-sized town on the other side of the lake called Santiago Atitlan . It's tucked into a cove so you can't see it from Panajachel, but it's the largest and least touristy of the main lakeside towns, so we went across to see it. Lake Atitlan is ringed with towns, villages, settlements and farms, and there's a lively ferry commerce in getting people from one place to another, as people may work in one town and live in another. The road, if it's not washed out, would take hours, but it only takes about half an hour to cross by boat, and it's a lot safer. Kathleen wanted to see Santiago because it's one of the abodes of the famed Maximon, patron saint of overindulgence, said to be a blend of San Simon, Pedro Alvarado, one of Cortez's most ruthless officers, and a Mayan deity. A life-sized wooden effigy of Maximon resides in a different home each year in Sanitiago, and worshipers (and tourists like us) are invited to make offerings of money, tobacco, and booze in return for miracles, blessings or photographs.

As our ferry docked at the edge of town, a boy offered to take us to see Maximon. We'd heard that we'd never find it by ourselves, so we bargained the price down from astronomical to merely outrageous, and he led us through winding streets, up the shabby barrios, into muddy alleys, finally entering a stick and mud and cinder block home with a corrugated tin roof and a dirt floor, into a candle lit room with a few people sitting on benches against the walls, and a crude wood carving of a man in the center. Maximon was dressed head to toe in a shabby western wool jacket, traditional pantaloons, six or eight neckties and a black felt hat, but with layers of beautifully woven cloth around his shoulders. A wooden altar before him held a tray containing offerings of money, which we added to, with other receptacles for cigarettes and bottles of aguardiente, the local rot-gut. We took seats on the dirt floor a few feet from Maximon. A man in the corner began tuning up an ancient guitar, and when he had it pretty close started an eerie repetitive chant with a couple of accompanying chords. As he sang, others entered the room, touched the hem of Maximon's woven garments, squeezed his left shoulder, crossed themselves, presented offerings, and found places. Occasionally other tourists would trickle in, snap a photo of Maximon for 5 Quetzals, and leave. Kathleen can smell a ritual brewing from a mile away, so we stayed put. As our ferry docked at the edge of town, a boy offered to take us to see Maximon. We'd heard that we'd never find it by ourselves, so we bargained the price down from astronomical to merely outrageous, and he led us through winding streets, up the shabby barrios, into muddy alleys, finally entering a stick and mud and cinder block home with a corrugated tin roof and a dirt floor, into a candle lit room with a few people sitting on benches against the walls, and a crude wood carving of a man in the center. Maximon was dressed head to toe in a shabby western wool jacket, traditional pantaloons, six or eight neckties and a black felt hat, but with layers of beautifully woven cloth around his shoulders. A wooden altar before him held a tray containing offerings of money, which we added to, with other receptacles for cigarettes and bottles of aguardiente, the local rot-gut. We took seats on the dirt floor a few feet from Maximon. A man in the corner began tuning up an ancient guitar, and when he had it pretty close started an eerie repetitive chant with a couple of accompanying chords. As he sang, others entered the room, touched the hem of Maximon's woven garments, squeezed his left shoulder, crossed themselves, presented offerings, and found places. Occasionally other tourists would trickle in, snap a photo of Maximon for 5 Quetzals, and leave. Kathleen can smell a ritual brewing from a mile away, so we stayed put.

A man motioned for a woman on the sidelines to sit in a wooden chair in front of Maximon’s effigy. He began chanting as he waved a can of burning copal, filling the small room with deliciously scented smoke. He passed it around his body, then handed it to the next man who did the same. The can of smoking copal was handed from man to man around the room until each one had smudged, taking care to wave it under their armpits. Two more men at Maximon's side made sure he had a lighted cigarette in his mouth which sometimes they exchanged for an unlit cigar, and once they poured a half bottle of the aguardiente into him, tilting him back to make sure none of it dripped onto his finery. Maximon's internal plumbing became another source of wonder to us both. Still chanting, the man in front opened a large wooden chest, took out some old tattered traditional clothing and after smudging each piece, placed layer after layer on the seated woman, ending with an old but fancy pair of men's dress shoes, size large, and a woven veil-like cloth on her head. On top of this he draped a huge black wool coat , pulling it down so that her face appeared to be completely covered. It was hot in the small room, now full of people and candles; she must have been suffocating. Kathleen knew it all along, but suddenly Rus realized this was a healing; the woman in front of Maximon was the patient, the older woman and young boy on the bench her mother and son, and the guy chanting with the copal was the shaman. A man motioned for a woman on the sidelines to sit in a wooden chair in front of Maximon’s effigy. He began chanting as he waved a can of burning copal, filling the small room with deliciously scented smoke. He passed it around his body, then handed it to the next man who did the same. The can of smoking copal was handed from man to man around the room until each one had smudged, taking care to wave it under their armpits. Two more men at Maximon's side made sure he had a lighted cigarette in his mouth which sometimes they exchanged for an unlit cigar, and once they poured a half bottle of the aguardiente into him, tilting him back to make sure none of it dripped onto his finery. Maximon's internal plumbing became another source of wonder to us both. Still chanting, the man in front opened a large wooden chest, took out some old tattered traditional clothing and after smudging each piece, placed layer after layer on the seated woman, ending with an old but fancy pair of men's dress shoes, size large, and a woven veil-like cloth on her head. On top of this he draped a huge black wool coat , pulling it down so that her face appeared to be completely covered. It was hot in the small room, now full of people and candles; she must have been suffocating. Kathleen knew it all along, but suddenly Rus realized this was a healing; the woman in front of Maximon was the patient, the older woman and young boy on the bench her mother and son, and the guy chanting with the copal was the shaman.

Photo above: Maximon's street, Below: Maximon's house

He chanted for a long time in his native tongue, the only Spanish the occasional name of a saint, pausing every few minutes to pour some aguardiente onto the floor where the candles would catch it and send a Whoosh! of flames high into the air. Some of the other people in the room talked casually from time to time while this was happening, but the man in front of us was all business, and we were all eyes. The room became a bubble, no other tourists came, and we both felt welcome and included. The man took a cigar from Maximon's tray, stuffed the whole thing into his mouth, and began to chew as he continued the ritual (the parts that didn't involve chanting, anyway). He chewed and chewed. When he had it chewed enough, he took a huge gulp of aguardiente, sloshed it around in his mouth with the masticated cigar, lifted the coat off of the woman's head, and spit in her face! Not symbolically, either, but a copious spray of brown juice and bits of tobacco, all over her face (and a little on Kathleen, who sat next to her). Then he peeled the clothes off her belly, both Maximon's and her own, spit on her bare skin, and rubbed the juice into it. Next he bared her back, spit out what was left, glanced over to a man at our side, who went to a window sill, picked out a tiny shard of glass and handed it to the shaman. He took the shard and made small punctures on her bare back where blood appeared, then he carefully made two more long, shallow cuts which became two lines of red, and poured aguardiente over them, rubbing her skin in circular motions. He ended by splashing the last of the bottle over the candles flames that flared up from the floor below. That was pretty much it; Maximon's clothes were returned to the chest, the woman pulled her huipil back down, her mother handed some money to the healer, and they left. When we left soon thereafter, the other people in the room met our eyes and smiled as we made our way to the door. We have no pictures of this, only the one you see of Maximon when we'd first arrived. We'd been sitting there for a long time, and our legs felt it, but we felt breathless and lucky to have seen more than an empty room and a wooden guy with a cigarette in his mouth, which is what someone we met said they saw half an hour later. He chanted for a long time in his native tongue, the only Spanish the occasional name of a saint, pausing every few minutes to pour some aguardiente onto the floor where the candles would catch it and send a Whoosh! of flames high into the air. Some of the other people in the room talked casually from time to time while this was happening, but the man in front of us was all business, and we were all eyes. The room became a bubble, no other tourists came, and we both felt welcome and included. The man took a cigar from Maximon's tray, stuffed the whole thing into his mouth, and began to chew as he continued the ritual (the parts that didn't involve chanting, anyway). He chewed and chewed. When he had it chewed enough, he took a huge gulp of aguardiente, sloshed it around in his mouth with the masticated cigar, lifted the coat off of the woman's head, and spit in her face! Not symbolically, either, but a copious spray of brown juice and bits of tobacco, all over her face (and a little on Kathleen, who sat next to her). Then he peeled the clothes off her belly, both Maximon's and her own, spit on her bare skin, and rubbed the juice into it. Next he bared her back, spit out what was left, glanced over to a man at our side, who went to a window sill, picked out a tiny shard of glass and handed it to the shaman. He took the shard and made small punctures on her bare back where blood appeared, then he carefully made two more long, shallow cuts which became two lines of red, and poured aguardiente over them, rubbing her skin in circular motions. He ended by splashing the last of the bottle over the candles flames that flared up from the floor below. That was pretty much it; Maximon's clothes were returned to the chest, the woman pulled her huipil back down, her mother handed some money to the healer, and they left. When we left soon thereafter, the other people in the room met our eyes and smiled as we made our way to the door. We have no pictures of this, only the one you see of Maximon when we'd first arrived. We'd been sitting there for a long time, and our legs felt it, but we felt breathless and lucky to have seen more than an empty room and a wooden guy with a cigarette in his mouth, which is what someone we met said they saw half an hour later.

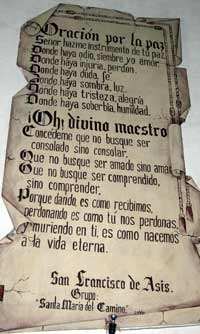

The Chicken Bus to Chichicastenango Market

And yes, we went to Chichi, or Chichicastenango, the biggest market in Central America, where everyone goes to buy anything Guatemalan, even if you're Guatemalan yourself! This place is sort of like the Grand Canyon of markets. Every Sunday, hundreds and hundreds of vendors descend on the town center and set up their stalls, selling largely textiles, but also artisanias, Mayan "artifacts", fruits and vegetables, dry goods and tourist junk. And thousands of people come to buy; lots of tourists, Central and North American and overseas, wholesale buyers, both local and for export, and locals as well. The pace is furious, the pressure is intense, and it's a hard place to tear yourself away from. Bring lots of money, and bargain hard! We took the chicken bus both ways from Panajachel to Chichi. It was worth the trip by itself to witness the skill of those drivers on the mountain roads, aided by the display of prayers and patron saints around their seats. It made us nervous, though, to see our driver cross himself before starting down a particularly steep and windy stretch of road. Their conductors are equally amazing, scaling up to the And yes, we went to Chichi, or Chichicastenango, the biggest market in Central America, where everyone goes to buy anything Guatemalan, even if you're Guatemalan yourself! This place is sort of like the Grand Canyon of markets. Every Sunday, hundreds and hundreds of vendors descend on the town center and set up their stalls, selling largely textiles, but also artisanias, Mayan "artifacts", fruits and vegetables, dry goods and tourist junk. And thousands of people come to buy; lots of tourists, Central and North American and overseas, wholesale buyers, both local and for export, and locals as well. The pace is furious, the pressure is intense, and it's a hard place to tear yourself away from. Bring lots of money, and bargain hard! We took the chicken bus both ways from Panajachel to Chichi. It was worth the trip by itself to witness the skill of those drivers on the mountain roads, aided by the display of prayers and patron saints around their seats. It made us nervous, though, to see our driver cross himself before starting down a particularly steep and windy stretch of road. Their conductors are equally amazing, scaling up to the  top of the bus at a stop to retrieve a bundle for a passenger, jumping onto the ladder as the bus pulls away, crawling along the roof to the front, and swinging back down into the open door and all the while remembering who has and who hasn't paid, and who needs how much change. These are old American schoolbuses designed for maybe 60 kids now carrying maybe 120 adults, plus kids and a few babies, and baggage on the roof. The other passengers were just as interesting, mostly Mayan men and women in their traditional clothing, a different weave for every town. We enjoyed being packed in among these folks for a few hours, having the chance to see so many beautiful, open faces up close, listening to the music of their voices. Most of these Mayan folks are pretty reserved, but we would catch them looking at us, too! After all, it's rather hard to ignore someone you are pressed tightly against and since it's at least three people to a seat, so six to a row, there's no aisle, and no apparent room to squeeze through. But people continue to get on and off the bus, and so it has to be done and somehow, inch by inch, people wedge themselves up and down the line. We did too. An absolutely Guatemalan experience! top of the bus at a stop to retrieve a bundle for a passenger, jumping onto the ladder as the bus pulls away, crawling along the roof to the front, and swinging back down into the open door and all the while remembering who has and who hasn't paid, and who needs how much change. These are old American schoolbuses designed for maybe 60 kids now carrying maybe 120 adults, plus kids and a few babies, and baggage on the roof. The other passengers were just as interesting, mostly Mayan men and women in their traditional clothing, a different weave for every town. We enjoyed being packed in among these folks for a few hours, having the chance to see so many beautiful, open faces up close, listening to the music of their voices. Most of these Mayan folks are pretty reserved, but we would catch them looking at us, too! After all, it's rather hard to ignore someone you are pressed tightly against and since it's at least three people to a seat, so six to a row, there's no aisle, and no apparent room to squeeze through. But people continue to get on and off the bus, and so it has to be done and somehow, inch by inch, people wedge themselves up and down the line. We did too. An absolutely Guatemalan experience!

Chichi market from Santo Tomas church steps, elders in red head cloths

One afternoon at Atitlan we took the "moto" out for a little trip to some of the other settlements around the lake, where we entered another world, completely unlike the touristy bustle of Panajachel and the hustle of the ferry docks. We drove up, and up through winding mountain roads, occasionally breaking out into a view of the lake that looked like we were dreaming it, then down as much as we'd climbed, low gear and brakes on the whole way, until we came to rich terraced farmland, a small village, more farmland on the other side, then more mountains. The road eventually turned to dirt, then rocks and ruts, went up a hill, then disappeared under a huge pile of dirt which lay across it. We saw ahead where it reconnected with more bad road, but we'd just passed a neat-looking village, so went back to have a look. We have never seen streets so narrow, as we drove into the higher elevations of San Antonio Polopo. Making our way along well-used cobbled streets where no automobile could possibly go, people looked in wonder and dogs and chickens scattered as we wound through their neighborhood. We feared one of these roads would end in a staircase and we'd have to turn around and try to retrace our way. But we soon broke out onto a street which brought us to the "centro", and parked the moto so Kathleen could go into the church (she loves churches; Rus loves waiting outside). When we returned to the moto, a woman nearby approached and asked Kathleen if she'd like to visit the women's weaving co-operative. Yes, we would, but were surprised that they had one in this little village. We left the moto in front of the church and followed her a few blocks up the hill, a few blocks to the right, then left, wondering how anyone could ever find this cooperative. Finally, stopping at a place that looked a lot like One afternoon at Atitlan we took the "moto" out for a little trip to some of the other settlements around the lake, where we entered another world, completely unlike the touristy bustle of Panajachel and the hustle of the ferry docks. We drove up, and up through winding mountain roads, occasionally breaking out into a view of the lake that looked like we were dreaming it, then down as much as we'd climbed, low gear and brakes on the whole way, until we came to rich terraced farmland, a small village, more farmland on the other side, then more mountains. The road eventually turned to dirt, then rocks and ruts, went up a hill, then disappeared under a huge pile of dirt which lay across it. We saw ahead where it reconnected with more bad road, but we'd just passed a neat-looking village, so went back to have a look. We have never seen streets so narrow, as we drove into the higher elevations of San Antonio Polopo. Making our way along well-used cobbled streets where no automobile could possibly go, people looked in wonder and dogs and chickens scattered as we wound through their neighborhood. We feared one of these roads would end in a staircase and we'd have to turn around and try to retrace our way. But we soon broke out onto a street which brought us to the "centro", and parked the moto so Kathleen could go into the church (she loves churches; Rus loves waiting outside). When we returned to the moto, a woman nearby approached and asked Kathleen if she'd like to visit the women's weaving co-operative. Yes, we would, but were surprised that they had one in this little village. We left the moto in front of the church and followed her a few blocks up the hill, a few blocks to the right, then left, wondering how anyone could ever find this cooperative. Finally, stopping at a place that looked a lot like  Maximon's house: stick and mud, sheet metal roof, hard dirt floor, she led us inside. There was one small window (without glass) facing the lake, but it was dark inside. Once our eyes adjusted to the light we noticed a table in the corner holding a stack of textiles, neatly folded. Oh, so this was the woman's cooperative! There were three other women there who greeted us with smiles as they worked, preparing thread for the loom. Olga, the woman who'd led us there, invited Kathleen to sit on a stool in the middle of the floor, and the women proceeded to dress her in the village's tightly woven huipil (blouse) and headdress, expertly twisting glittering ribbons with woven scarves in her hair, around and around until they all became a crown, accented by two ribbons trailing color down her back. It was quite a sight - unfortunately the camera didn't capture it well in the dim light. Kathleen didn't buy the huipil that Olga wanted to sell her but she did buy a some textiles as gifts to bring home and a long, glittery ribbon for herself, all tightly woven in the distinctive style of that village. Some time later, far from San Antonio Polopo near the border with Honduras, a woman we saw just beamed when Kathleen recognized her home town by the clothes she wore. Maximon's house: stick and mud, sheet metal roof, hard dirt floor, she led us inside. There was one small window (without glass) facing the lake, but it was dark inside. Once our eyes adjusted to the light we noticed a table in the corner holding a stack of textiles, neatly folded. Oh, so this was the woman's cooperative! There were three other women there who greeted us with smiles as they worked, preparing thread for the loom. Olga, the woman who'd led us there, invited Kathleen to sit on a stool in the middle of the floor, and the women proceeded to dress her in the village's tightly woven huipil (blouse) and headdress, expertly twisting glittering ribbons with woven scarves in her hair, around and around until they all became a crown, accented by two ribbons trailing color down her back. It was quite a sight - unfortunately the camera didn't capture it well in the dim light. Kathleen didn't buy the huipil that Olga wanted to sell her but she did buy a some textiles as gifts to bring home and a long, glittery ribbon for herself, all tightly woven in the distinctive style of that village. Some time later, far from San Antonio Polopo near the border with Honduras, a woman we saw just beamed when Kathleen recognized her home town by the clothes she wore.

Photos above: San Antonio Popolo nestled in a cove, Young onions and corn grow on terraces wherever there's room to plant them

Moving On

After 15 days in Guatemala, the achingly beautiful land and the rich culture we'd barely explored, we feel like we'd better either spend the rest of our lives here, or think about moving on. Even with a year or so left, that map of South America looks pretty big, especially compared to tiny Central America! It's early July, and with our son Jamie's wedding in September, we're wondering how to make reservations to fly back to California when we don't even know where we'll be. We want to be done with the most the challenging segment of the trip, the ferry and flight from Panama to South America. On the road, logistics that would be simple at home become much more difficult, without an address or phone, or knowing where you'll be tomorrow. We decided to step up our pace a bit. Photo: San Antonio women washing clothes, After 15 days in Guatemala, the achingly beautiful land and the rich culture we'd barely explored, we feel like we'd better either spend the rest of our lives here, or think about moving on. Even with a year or so left, that map of South America looks pretty big, especially compared to tiny Central America! It's early July, and with our son Jamie's wedding in September, we're wondering how to make reservations to fly back to California when we don't even know where we'll be. We want to be done with the most the challenging segment of the trip, the ferry and flight from Panama to South America. On the road, logistics that would be simple at home become much more difficult, without an address or phone, or knowing where you'll be tomorrow. We decided to step up our pace a bit. Photo: San Antonio women washing clothes,

Below: Xela's lovely Parque Central

Xela and Fuentes Georgina

We left Atitlan headed for Xela, pronounced Shayla, a beautiful town with a beautiful name. Its real name is Quetzaltenango, but nobody uses it. Just when you think you can't stand another lovely colonial city in the highlands, another one comes along, with its spacious, open central plaza, grand old Spanish stone buildings, inviting cafes and says, "Come on, sweety, just a little bit closer and snuggle up; we're gonna have a goood time, and I even have an ATM." We flirted and did some light petting with Xela, but left before she even got us to third base because when we saw where we were going to sleep, we knew we'd regret it in the morning. And we just weren't ready to have our hearts broken again, so soon after Atitlan. We just wanted a casual one-nighter this time, and had an invitation from her cousin Georgina, who lived at a hot springs in the mountains nearby, so we tore ourselves away and headed for the hills. Besides, Xela's ATM was out of cash, and so were we. We left Atitlan headed for Xela, pronounced Shayla, a beautiful town with a beautiful name. Its real name is Quetzaltenango, but nobody uses it. Just when you think you can't stand another lovely colonial city in the highlands, another one comes along, with its spacious, open central plaza, grand old Spanish stone buildings, inviting cafes and says, "Come on, sweety, just a little bit closer and snuggle up; we're gonna have a goood time, and I even have an ATM." We flirted and did some light petting with Xela, but left before she even got us to third base because when we saw where we were going to sleep, we knew we'd regret it in the morning. And we just weren't ready to have our hearts broken again, so soon after Atitlan. We just wanted a casual one-nighter this time, and had an invitation from her cousin Georgina, who lived at a hot springs in the mountains nearby, so we tore ourselves away and headed for the hills. Besides, Xela's ATM was out of cash, and so were we.

Fuentes Georgina wasn't easy to find, it turned out, like so many good things. It took over two hours wandering lost through the mountains. At one point we came a fork in the one-lane track, with no idea which way to go. A metal sign lay on the ground but it was blank. Kathleen got out, turned it over, and it said Fuentes Georgina --->, which could only mean right, unless you pointed the arrow left, but then the words would be upside down. We're pretty quick at figuring things like this out. Arriving at last at a solid steel closed and locked gate and a sign that said "Cerrado", our spirits fell. But some men slid the peephole open to have a look, and said we could come in and spend the night. This was good, especially since it was almost dark, we were tired and frazzled, and there was nowhere to turn around on this winding, precipitous road. We were prepared to beg, but didn't even have to do more than ask. We found a place to park, but they said we we'd have to leave in the morning, as they were expecting lots of people and didn't have enough parking. Then we got on our swimsuits and found our way to the pools. Georgina is high in the mountains, surrounded by lush tropical forest, which accounts for much of its beauty. There are cabins to rent, a spacious restaurant next to a large pool, fed by hot sulphur seeps from the cliff wall on one side. We spent a luscious hour or so enjoying the perfect water, a full moon, and the cool night air, mostly with the place to ourselves. Fuentes Georgina wasn't easy to find, it turned out, like so many good things. It took over two hours wandering lost through the mountains. At one point we came a fork in the one-lane track, with no idea which way to go. A metal sign lay on the ground but it was blank. Kathleen got out, turned it over, and it said Fuentes Georgina --->, which could only mean right, unless you pointed the arrow left, but then the words would be upside down. We're pretty quick at figuring things like this out. Arriving at last at a solid steel closed and locked gate and a sign that said "Cerrado", our spirits fell. But some men slid the peephole open to have a look, and said we could come in and spend the night. This was good, especially since it was almost dark, we were tired and frazzled, and there was nowhere to turn around on this winding, precipitous road. We were prepared to beg, but didn't even have to do more than ask. We found a place to park, but they said we we'd have to leave in the morning, as they were expecting lots of people and didn't have enough parking. Then we got on our swimsuits and found our way to the pools. Georgina is high in the mountains, surrounded by lush tropical forest, which accounts for much of its beauty. There are cabins to rent, a spacious restaurant next to a large pool, fed by hot sulphur seeps from the cliff wall on one side. We spent a luscious hour or so enjoying the perfect water, a full moon, and the cool night air, mostly with the place to ourselves.

Next morning was a different story; people were beginning to arrive by the carload and van load. It was, after all, the weekend and this was the premier hot springs of Guatemala. We moved our rig to make more room available, then returned to the pool for a farewell soak, where we had a fun time with a couple of young Americans who had come there on an outing with their teacher from a Spanish school in Xela. One of them, Bethany, had started from zero only a month before, and was already speaking better than Rus, who has been messing around with the language for years. She also spoke French, which she said helped. But Rus also speaks French so what's his problem? Before heading out, we went once more to the pool to have a look. It had turned into a real cannibal stew! We were grateful we'd come the night before. Next morning was a different story; people were beginning to arrive by the carload and van load. It was, after all, the weekend and this was the premier hot springs of Guatemala. We moved our rig to make more room available, then returned to the pool for a farewell soak, where we had a fun time with a couple of young Americans who had come there on an outing with their teacher from a Spanish school in Xela. One of them, Bethany, had started from zero only a month before, and was already speaking better than Rus, who has been messing around with the language for years. She also spoke French, which she said helped. But Rus also speaks French so what's his problem? Before heading out, we went once more to the pool to have a look. It had turned into a real cannibal stew! We were grateful we'd come the night before.

View from pool area at Fuentes Georgina

The Sugar Refinery- Sweet!

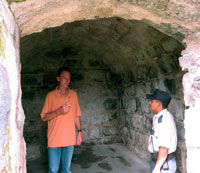

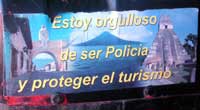

Next we drove to Santa Lucia Cotzumalguapa (easier to say than read), where a police motorcycle motioned us over. We were prepared for another mordida, for some real or fabricated infraction, but instead they asked where we were going and escorted us there, through the town and several kilometers into to country to the El Baul sugar refinery, where they spoke to the guards, who opened the gate for us. They seemed embarrassed by our offer of a tip, but we insisted they take it and thanked them profusely for their help, since we were utterly lost when they came along. This huge refinery, which shut down three years ago, is also the site of the Museo El Baul, which we'd come to see. It's an open-air collection of Pipil stone sculptures uncovered from the fields of the company's sugar plantation over the years. We asked and were given permission by the guard to stay for the night, drove through the abandoned refinery to the museum, found a concrete slab nearby, and went out for a look. There were some of the finest and best-preserved stone sculptures we've seen, some displayed in the open and some under a protective roof, no interpretation, no admission charge, no one else around. The scene was made even more surreal by its setting, in the middle of a huge abandoned refinery, its machinery rusting, the jungle beginning to reclaim it just as it did the abandoned Mayan cities before. Next we drove to Santa Lucia Cotzumalguapa (easier to say than read), where a police motorcycle motioned us over. We were prepared for another mordida, for some real or fabricated infraction, but instead they asked where we were going and escorted us there, through the town and several kilometers into to country to the El Baul sugar refinery, where they spoke to the guards, who opened the gate for us. They seemed embarrassed by our offer of a tip, but we insisted they take it and thanked them profusely for their help, since we were utterly lost when they came along. This huge refinery, which shut down three years ago, is also the site of the Museo El Baul, which we'd come to see. It's an open-air collection of Pipil stone sculptures uncovered from the fields of the company's sugar plantation over the years. We asked and were given permission by the guard to stay for the night, drove through the abandoned refinery to the museum, found a concrete slab nearby, and went out for a look. There were some of the finest and best-preserved stone sculptures we've seen, some displayed in the open and some under a protective roof, no interpretation, no admission charge, no one else around. The scene was made even more surreal by its setting, in the middle of a huge abandoned refinery, its machinery rusting, the jungle beginning to reclaim it just as it did the abandoned Mayan cities before.

Returning to our rig, we were met by another guard who regretted to inform us that they did not have the authority to grant us permission to park inside the property for the night. We said it was important for us to have security, so where could we go, and he said we could park just outside the gates, where they could still watch over us. After we had reparked, we chatted with the guards for a bit. The one who'd kicked us out, Victor, asked if we'd like to see the old hydroelectric plant nearby. Rus was eager to see it so we followed him across the road and down a path to a gate. Another guard let us through, and we continued down the path to a clear, fast river with an ancient concrete building at its bank. Victor told us this was the original plant for the refinery, built in 1914 and still operational. Through a gap in the door, we could see the ancient turbines and a giant diesel generator for emergencies. There were mango and avocado trees dropping fruit all over, and Victor invited us to take some. With the river rushing by and an early evening light shower to cool us in this unusual blend of industry and natural beauty, we felt pretty good. Returning to our rig, we were met by another guard who regretted to inform us that they did not have the authority to grant us permission to park inside the property for the night. We said it was important for us to have security, so where could we go, and he said we could park just outside the gates, where they could still watch over us. After we had reparked, we chatted with the guards for a bit. The one who'd kicked us out, Victor, asked if we'd like to see the old hydroelectric plant nearby. Rus was eager to see it so we followed him across the road and down a path to a gate. Another guard let us through, and we continued down the path to a clear, fast river with an ancient concrete building at its bank. Victor told us this was the original plant for the refinery, built in 1914 and still operational. Through a gap in the door, we could see the ancient turbines and a giant diesel generator for emergencies. There were mango and avocado trees dropping fruit all over, and Victor invited us to take some. With the river rushing by and an early evening light shower to cool us in this unusual blend of industry and natural beauty, we felt pretty good.

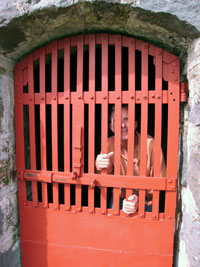

We returned to our rig to make dinner and relax, offered sodas to the guards, which they gladly accepted. We didn't want to tempt them with beer when they were on duty. After dinner, outside chatting with the guards again, a man drove up in a car who was obviously the jefe, joined us in conversation, and invited us back inside the gates, which we gratefully accepted, as we were parked in the grass in an ant-infested area. We'd had a very secure night's sleep, ant-free, and in the morning began to walk around the refinery buildings, which we'd gotten permission to do from the jefe. Victor soon found us, and began to show us all around the grounds and inside the buildings, explaining the refining process from the time the cane arrived in huge truck trailers until it was shipped out as white sugar. We surprised a flock of green parrots roosting in the roof beams of a huge metal warehouse, and they were beautiful as they flew out into the morning sky. Equally interesting, he showed us the living quarters of the "esclavos"(slaves), as he called them, for they were worked hard and paid little. They slept packed into huge semi-open bunkhouses, on metal bunk beds that looked like prison furniture, and ate in refectories seated on long rows of tables with benches. There was another building which housed a market with concrete stalls, where the workers could buy their own food and sundry items for personal use (if they could afford them); it seemed a worker could live his whole life in this refinery, and indeed, there was even a brick church, a cemetery, and a jail! We returned to our rig to make dinner and relax, offered sodas to the guards, which they gladly accepted. We didn't want to tempt them with beer when they were on duty. After dinner, outside chatting with the guards again, a man drove up in a car who was obviously the jefe, joined us in conversation, and invited us back inside the gates, which we gratefully accepted, as we were parked in the grass in an ant-infested area. We'd had a very secure night's sleep, ant-free, and in the morning began to walk around the refinery buildings, which we'd gotten permission to do from the jefe. Victor soon found us, and began to show us all around the grounds and inside the buildings, explaining the refining process from the time the cane arrived in huge truck trailers until it was shipped out as white sugar. We surprised a flock of green parrots roosting in the roof beams of a huge metal warehouse, and they were beautiful as they flew out into the morning sky. Equally interesting, he showed us the living quarters of the "esclavos"(slaves), as he called them, for they were worked hard and paid little. They slept packed into huge semi-open bunkhouses, on metal bunk beds that looked like prison furniture, and ate in refectories seated on long rows of tables with benches. There was another building which housed a market with concrete stalls, where the workers could buy their own food and sundry items for personal use (if they could afford them); it seemed a worker could live his whole life in this refinery, and indeed, there was even a brick church, a cemetery, and a jail!

Victor, though a security guard, was very knowledgeable about the refinery's operations, having been a guard there for years when it was still operating. He also knew the names and uses of many of the plants and trees indigenous to the area, pointing them out as we went. When we mentioned that he seemed to have a great love of nature, and that we'd noticed how he'd gently brushed off a large spider that had landed on Rus the evening before, Victor smiled and nodded shyly. Thanking him for his time and generosity, we asked if we could tip him something as a gesture of appreciation. He graciously declined in a way that left no doubt that he'd done it because he wanted to, out of our interest and his own. Again and again, in spite of overwhelming and repeated evidence, we are surprised that we are often as interesting to the people we meet as they are to us. And so it was late morning when we finally said our good-byes at the Ingenio El Baul, skipping a nearby site with carved stones in the tall cane fields, where people still sacrifice chickens as part of regular Sunday services. Our guard friends said it was unsafe because of robbers, and besides, sacrificing chickens is old hat to us by now! Victor, though a security guard, was very knowledgeable about the refinery's operations, having been a guard there for years when it was still operating. He also knew the names and uses of many of the plants and trees indigenous to the area, pointing them out as we went. When we mentioned that he seemed to have a great love of nature, and that we'd noticed how he'd gently brushed off a large spider that had landed on Rus the evening before, Victor smiled and nodded shyly. Thanking him for his time and generosity, we asked if we could tip him something as a gesture of appreciation. He graciously declined in a way that left no doubt that he'd done it because he wanted to, out of our interest and his own. Again and again, in spite of overwhelming and repeated evidence, we are surprised that we are often as interesting to the people we meet as they are to us. And so it was late morning when we finally said our good-byes at the Ingenio El Baul, skipping a nearby site with carved stones in the tall cane fields, where people still sacrifice chickens as part of regular Sunday services. Our guard friends said it was unsafe because of robbers, and besides, sacrificing chickens is old hat to us by now!

Beautiful Antigua

We pointed ourselves in the direction of Antigua, and enjoyed one of our most scenic drives, and good roads to take us there. The volcanoes surrounding the city are visible for much of the drive, and once we even saw a brown plume of smoke belch from Volcan de Fuego, aptly named. Entering the city, we were not prepared to see so many of its fine old buildings in ruins, but that's what people come to see: 300-year-old buildings lying in rubble. We have to admit, once you get used to it, it's pretty neat, somewhat like the Roman ruins. Antigua used to be Guatemala's capitol, but is unfortunately situated close to a fault zone and suffered periodic damage and disruption. Finally in 1773 a series of large quakes pretty much leveled the city, the capitol was moved three years later to its present site. Orders were given to abandon the city completely, but some refused to leave and eventually the town began to rebuild. The ruins from 1773 are carefully preserved, though, worth far more in tourist dollars than if they were still standing in perfect condition. Antigua is also home to the largest concentration of Spanish language schools in the universe, some 75 of them, so if you can't find a place to study Spanish in Antigua, you're just pathetic, that's all. We pointed ourselves in the direction of Antigua, and enjoyed one of our most scenic drives, and good roads to take us there. The volcanoes surrounding the city are visible for much of the drive, and once we even saw a brown plume of smoke belch from Volcan de Fuego, aptly named. Entering the city, we were not prepared to see so many of its fine old buildings in ruins, but that's what people come to see: 300-year-old buildings lying in rubble. We have to admit, once you get used to it, it's pretty neat, somewhat like the Roman ruins. Antigua used to be Guatemala's capitol, but is unfortunately situated close to a fault zone and suffered periodic damage and disruption. Finally in 1773 a series of large quakes pretty much leveled the city, the capitol was moved three years later to its present site. Orders were given to abandon the city completely, but some refused to leave and eventually the town began to rebuild. The ruins from 1773 are carefully preserved, though, worth far more in tourist dollars than if they were still standing in perfect condition. Antigua is also home to the largest concentration of Spanish language schools in the universe, some 75 of them, so if you can't find a place to study Spanish in Antigua, you're just pathetic, that's all.

We parked on a shady side street and walked to the spacious and beautiful Parque Central, where we asked at the tourism office if they knew of anywhere we could camp. Why figure everything out by ourselves? In the larger tourist towns like Antigua, they've seen it all and know where to send you. We were given three possibilities, and found a perfect place, a private "parqueo" right across from the bus terminal and market, a ruin on one side, a cemetery on the other, and a forest to the rear. The caretaker asked if we'd been sent there by a German couple in a big truck who'd been there six weeks ago, and pressing him for more information, we recognized our neighbors from San Miguel De Allende two months before. Not too many rvs come to Antigua, we guessed, if the last one was a month and a half before. A parqueo is just a commercial parking lot, no services expected, none given, but they have some security, and this one was exceptionally nice, within walking distance to everything we needed. We parked on a shady side street and walked to the spacious and beautiful Parque Central, where we asked at the tourism office if they knew of anywhere we could camp. Why figure everything out by ourselves? In the larger tourist towns like Antigua, they've seen it all and know where to send you. We were given three possibilities, and found a perfect place, a private "parqueo" right across from the bus terminal and market, a ruin on one side, a cemetery on the other, and a forest to the rear. The caretaker asked if we'd been sent there by a German couple in a big truck who'd been there six weeks ago, and pressing him for more information, we recognized our neighbors from San Miguel De Allende two months before. Not too many rvs come to Antigua, we guessed, if the last one was a month and a half before. A parqueo is just a commercial parking lot, no services expected, none given, but they have some security, and this one was exceptionally nice, within walking distance to everything we needed.

Women from Santa Catarina Popolo on Lake Atitlan sell textiles on the streets of Antigua (you can spot them by their colors) Women from Santa Catarina Popolo on Lake Atitlan sell textiles on the streets of Antigua (you can spot them by their colors)

Antigua is truly a special place, loved by millions of travelers, and several thousand of those millions were there when we were. Somehow, the city absorbs them all; there are so many stores, hotels and restaurants, and the town is laid out in such a spacious, organized way compared to say, San Miguel de Allende, that people don't get in each other's way. They say the Spaniards spared no expense in building Antigua, and it still shows today, even with all the ruins. For several days, we enjoyed walking the streets, visiting museums, eating good food, shopping for textiles in Nim Po't, a great Mayan collective store, just being tourists.

The ruins of Las Capuchinas (church and convent) and La Recoleccion (church and convent)

|

|

We were disappointed, though, since we were there at the time of the Mexican presidential elections, to learn that Lopez Obrador, the progressive candidate, had lost by the slimmest of margins to Felipe Calderon, the right wing candidate who had vastly outspent him. Calderon had hired Dick Morris, an American political consultant, to turn his campaign around in the final months when the polls showed Lopez Obrador ahead. This guy, Morris, had previously managed Clinton's re-election campaign, but was fired for having a prostitute listen in on conversations with his boss to impress her. He then switched parties (if he ever had one) and became a commentator for Fox News. Working for Calderon, Morris engineered a Mexican version of the Swiftboat Veterans for Truth, saturating the airwaves with lies and rumors. Like it does in the U.S., where uneducated people get their news and form their opinions from TV, it worked: Calderon squeaked past Lopez Obrador by .6% of the vote. We were disappointed, though, since we were there at the time of the Mexican presidential elections, to learn that Lopez Obrador, the progressive candidate, had lost by the slimmest of margins to Felipe Calderon, the right wing candidate who had vastly outspent him. Calderon had hired Dick Morris, an American political consultant, to turn his campaign around in the final months when the polls showed Lopez Obrador ahead. This guy, Morris, had previously managed Clinton's re-election campaign, but was fired for having a prostitute listen in on conversations with his boss to impress her. He then switched parties (if he ever had one) and became a commentator for Fox News. Working for Calderon, Morris engineered a Mexican version of the Swiftboat Veterans for Truth, saturating the airwaves with lies and rumors. Like it does in the U.S., where uneducated people get their news and form their opinions from TV, it worked: Calderon squeaked past Lopez Obrador by .6% of the vote.

The highlands are beautiful, the colonial cities are too, but we wanted to see a different side of this country that was stealing our hearts, and places that weren't quite so popular. We packed up and drove out of our parqueo, headed for Guatemala's Pacific Coast and the small town of Monterico.

Trouble!

People love to hear about things that happen to others, but no one wants trouble of their own. We're no exception, of course, and yet we figured we'd have our share of problems on a journey of this magnitude. Crossing the Iztapa ferry we ran into our biggest problem yet. If you don't have experience with RVs then you may not fully appreciate this part, but here's what happened on the way to Monterico: People love to hear about things that happen to others, but no one wants trouble of their own. We're no exception, of course, and yet we figured we'd have our share of problems on a journey of this magnitude. Crossing the Iztapa ferry we ran into our biggest problem yet. If you don't have experience with RVs then you may not fully appreciate this part, but here's what happened on the way to Monterico:

We think our graywater tank (which holds wastewater from the sinks and shower) may have already come loose on the bumpy dirt road leading to the ferry "dock" at Iztapa. We boarded the ferry ok and made it to the opposite shore, the only mishap was Ziggy jumping overboard to cool off. The boat had to stop while we let her catch up and hauled her back aboard. But backing off the boat, the tank caught on the ramp and broke completely loose, flooding the  deck with our grey water, which then flowed into the river. About 30 gallons of it!! Thank God it wasn't the blackwater tank ( from the toilet) was all we could think, then we realized what a jam we were in. We emptied the tank completely, disconnected the drain valve cable (it was already broken) tore off the sensor wires (they didn't work anyway) threw the empty tank into the rig and crept off the ferry to dry land. The tank had been attached at the factory with weak aluminum straps, not stainless steel, and the rough roads and topes had finally done them in. deck with our grey water, which then flowed into the river. About 30 gallons of it!! Thank God it wasn't the blackwater tank ( from the toilet) was all we could think, then we realized what a jam we were in. We emptied the tank completely, disconnected the drain valve cable (it was already broken) tore off the sensor wires (they didn't work anyway) threw the empty tank into the rig and crept off the ferry to dry land. The tank had been attached at the factory with weak aluminum straps, not stainless steel, and the rough roads and topes had finally done them in.

Right: That black speck is Ziggy trying to catch up to the ferry

Below, right: Enrique to the rescue!

It's amazing how quickly plans change. We'd been excited about visiting this remote town and being on the Pacific shore again after so long in the Highlands, and in just a few seconds we cared only about finding a plumber and a hardware store in a place where neither was likely. Driving along the narrow road to Monterico, a narrow spit of land lined with lufa farms but no services, on one side mangrove swamps, on the other the Pacific ocean, we came to a tavern curiously called "No Way, Jose", owned by a man named Julio, who we'd just met while waiting for the ferry. Julio was outside and we stopped, knowing he had lived in the states and spoke English. We told him about our problem and that we needed a plumber. He said he'd call a guy in the next village who could help us, and wanted to know every detail so he could explain it over the phone. A long conversation ensued between Julio and Enrique, the plumber, who said he'd meet us on his motorcycle at the next gas station and take us to his place. We thanked Julio profusely and drove off to meet this plumber. It's amazing how quickly plans change. We'd been excited about visiting this remote town and being on the Pacific shore again after so long in the Highlands, and in just a few seconds we cared only about finding a plumber and a hardware store in a place where neither was likely. Driving along the narrow road to Monterico, a narrow spit of land lined with lufa farms but no services, on one side mangrove swamps, on the other the Pacific ocean, we came to a tavern curiously called "No Way, Jose", owned by a man named Julio, who we'd just met while waiting for the ferry. Julio was outside and we stopped, knowing he had lived in the states and spoke English. We told him about our problem and that we needed a plumber. He said he'd call a guy in the next village who could help us, and wanted to know every detail so he could explain it over the phone. A long conversation ensued between Julio and Enrique, the plumber, who said he'd meet us on his motorcycle at the next gas station and take us to his place. We thanked Julio profusely and drove off to meet this plumber.

A few kilometers on, we saw Enrique, who led us down a sand track toward the ocean, where it turned off to his house. We said we needed to dump and flush our black water tank before he could work on the (shared) plumbing so with his neighbor's permission we dug a deep hole at a trash burning site and got that nasty job done, unfortunately with lots of curious onlookers. Can anything be more embarrassing than dumping 5 days worth of your pee and poop in the ground in front of an audience? It's sort of like going to the john with a crowd watching, but smells much worse. That done, Enrique quickly assessed the problem and got to work. With minimal tools, a bucket of miscellaneous pipe fittings and some insulated wire salvaged from old jumper cables to A few kilometers on, we saw Enrique, who led us down a sand track toward the ocean, where it turned off to his house. We said we needed to dump and flush our black water tank before he could work on the (shared) plumbing so with his neighbor's permission we dug a deep hole at a trash burning site and got that nasty job done, unfortunately with lots of curious onlookers. Can anything be more embarrassing than dumping 5 days worth of your pee and poop in the ground in front of an audience? It's sort of like going to the john with a crowd watching, but smells much worse. That done, Enrique quickly assessed the problem and got to work. With minimal tools, a bucket of miscellaneous pipe fittings and some insulated wire salvaged from old jumper cables to  replace the flimsy aluminum straps, he made a fix that got us on the road again in a couple of hours, and may just last us the rest of the trip. We've been impressed how resourceful people are here in Latin America, how repairs are done not according to the best hypothetical solution, but according to what resources are available, right now, to fix the problem. In the U.S., with so many parts, materials and specialists at hand, the quickest and easiest fix is often dismissed, and so repairs become complicated, lengthly and expensive. Enrique had no idea what to charge us, so we gave him the equivalent of about $40 US, probably overly generous, but then so was he. Kathleen had fun with Enrique's family while we worked on the rig, as you can see. We like to get people's addresses to send them prints when we get home, as they don't get family portraits very often. Neither do we, for that matter! replace the flimsy aluminum straps, he made a fix that got us on the road again in a couple of hours, and may just last us the rest of the trip. We've been impressed how resourceful people are here in Latin America, how repairs are done not according to the best hypothetical solution, but according to what resources are available, right now, to fix the problem. In the U.S., with so many parts, materials and specialists at hand, the quickest and easiest fix is often dismissed, and so repairs become complicated, lengthly and expensive. Enrique had no idea what to charge us, so we gave him the equivalent of about $40 US, probably overly generous, but then so was he. Kathleen had fun with Enrique's family while we worked on the rig, as you can see. We like to get people's addresses to send them prints when we get home, as they don't get family portraits very often. Neither do we, for that matter!

Photo above left: Astrid, Glilian, Carlos, Jennifer, and neighbor Anna Rebecca, Above right: two hours later

Monterico

After our tank was reattached, we continued the last few kilometers to the coastal community of Monterico, on the western Pacific coast. Our first order of business coming into a more off-the-track town is to find a place to camp. Often a boy, (never a girl), offers to help, and as we came to the first dirt cross street, a young hustler about 8 years old leaped on our running board, to take us around the town. Unless we know where we're going, which is hardly ever, we'll often gladly accept the offer in exchange for a small tip. Sometimes a hotel will have a lot big enough to park in for a small fee, and sometimes if we're really lucky we can run an extension cord to a spare outlet. In Monterico, however, we had no such luck. Though there was very little business this time of year, even the hotels that had room for us didn't know what to do with a customer that doesn't want a room, just a place to park and maybe an outlet. It's not listed on the rate sheet. After our tank was reattached, we continued the last few kilometers to the coastal community of Monterico, on the western Pacific coast. Our first order of business coming into a more off-the-track town is to find a place to camp. Often a boy, (never a girl), offers to help, and as we came to the first dirt cross street, a young hustler about 8 years old leaped on our running board, to take us around the town. Unless we know where we're going, which is hardly ever, we'll often gladly accept the offer in exchange for a small tip. Sometimes a hotel will have a lot big enough to park in for a small fee, and sometimes if we're really lucky we can run an extension cord to a spare outlet. In Monterico, however, we had no such luck. Though there was very little business this time of year, even the hotels that had room for us didn't know what to do with a customer that doesn't want a room, just a place to park and maybe an outlet. It's not listed on the rate sheet.

At a place called "Johnny's" the clerk called a guy over from the volleyball game on the beach and although he didn't look too happy about it, Selso took Kathleen to a hotel next door, where they also said no. By this time he seemed to have accepted responsibility to help us find a place, that's how people are here, once involved they stay til it's over and usually get something out of it for their trouble. Selso said his brother, Francisco had room for us to park in his front yard a few blocks away. That sounded good to us and so he lead Kathleen down the path, Rus following in the rig. Francisco, a local shrimp fisherman with a large family was suddenly 50 Quetzals to the better, and we had a place to stay, with water from his well to fill our tank. Selso, it turned out, was a part-time guide, also a lifeguard, plus owning a washer  and dryer automatically put him into business as a laundry service. He offered to take us out on the river at daybreak to see the mangrove swamps and wildlife, then to the sea turtle, cayman, green iguana and garfish restoration facility afterward, all for a reasonable price. We set a time, then took a stroll through town and ate dinner at a place called the Pelicano which had killer pina coladas and a pet pelican. We fell asleep to a violent thunder and lightning show, accompanied by one of the all-night drenchers this region is famous for. Francisco's yard> and dryer automatically put him into business as a laundry service. He offered to take us out on the river at daybreak to see the mangrove swamps and wildlife, then to the sea turtle, cayman, green iguana and garfish restoration facility afterward, all for a reasonable price. We set a time, then took a stroll through town and ate dinner at a place called the Pelicano which had killer pina coladas and a pet pelican. We fell asleep to a violent thunder and lightning show, accompanied by one of the all-night drenchers this region is famous for. Francisco's yard>

At 6:00 next morning Selso came for us accompanied by two "chicas" from London on vacation. We walked together in the first light of morning along dirt streets to the river shore, lined with fishermen's pirogues and small ferries which ran people back and forth, as Monterico is on a narrow spit, cut off from the mainland by the river. We boarded his brother's pirogue, after bailing about 4 inches of water from the previous evening's storm, and Selso expertly poled us along the shallow channels through the mangrove swamps in the estuary as the natural world awakened, and the sun lit up the distant volcanoes we'd left in Antigua the day before. We learned that Selso is a single dad with three young children he is raising by himself. He impressed us as smart, sophisticated and knowledgeable, especially about the plants and animals of the region. Two of his 8 siblings have moved to the city and he said a bit wistfully that they will never come back, but he seems happy living in a sleepy tropical village surrounded by friends and family and doing work that allows him great flexibility and contact with nature.